The news is just too much, sometimes. The system seems broken. Which system? Your pick. But here is what art is for: not escape, exactly, but the slant rhyme that lets you stop considering the circumstances of your condition. Which, sometimes, enables you to consider the circumstances of our condition.

As an “Enthusiasm,” an inconsequential scene from The Wire may seem too small and too obvious. The Baltimore police procedural created by former reporter David Simon hardly needs my recommendation. It’s canon from the golden age of prestige television. (2000-2023, says Wiki. RIP.) The Wire’s six-season run concluded long before that, in 2008. The last episode aired in March of that year, before Barack Obama had even clinched the nomination that would make him president. Ancient history. Perfect then, if you want to get away from 2026. Especially if you nonetheless feel the tug of the now that won’t let you quite forget that is, indeed, every day, relentlessly 2026.

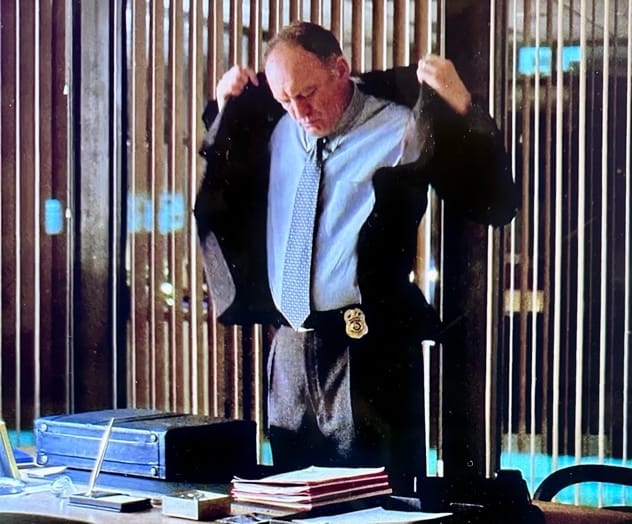

There’s a tiny, seemingly inconsequential moment in Episode 6 of Season One to which I’ve found myself returning. It begins around minute 25. An external shot of police headquarters cuts away to show the careerist Baltimore police commander, Rawls—more of a series antagonist than the drug dealers—putting on his jacket to head home for the night. He glances down at a stack of three red folders on his desk, case files the season's hero, Detective McNulty, has left for him to review. Picks one up, glances at another. Then he looks up and shouts “Jay!”--his cynical sergeant, his toady. That’s it. The entire scene is about 25 seconds. Why do they give it any time at all?

Two scenes later, we learn that what seemed meaningless was actually exposition. Sergeant Jay tells Detective McNulty that Commander Rawls wants arrests on the cases in the red folders, a move McNulty, Jay, and Rawls all know will improve the stats, the quotas, the higher-ups value even as they’ll damage the larger case against a drug kingpin. But if the tiny scene was in service of plot exposition—if it was there to explain, to move things along--why make it so quiet, and why separate from the answer it’s meant to provide?

I watched again, and again. Most of the scene is dedicated to Rawls putting on his jacket and adjusting the lapels.

He’s a vain man, almost completely uninterested in police work. He’s an apparatchik. He wants the system to work, which is to say that he wants to get a paycheck and to rise through the ranks. All this is summed up in the way the actor who plays Rawls, John Doman, puts on his dark grey jacket. He lets out an irritated sigh, gets his arms through the sleeves, and shrugs the coat up with his shoulders, still holding the puffed cheek expression of his sigh. Then he adjusts the lapels three times. He’s too lazy to put the jacket on properly, but he wants it to look “good.” Officious. All along he’s staring at the stack of case folders. Again, too lazy to really engage—three cleared cases—but vain enough to want their rewards, the credit he’ll receive for arrests that amount to little more than churn and punishment for those who take the work that’s available to them.

He drops his hands, staring at the folders. We notice that his belt is around his belly button--that although he’s in his late 50s, reasonably fit, aggressive enough in his demeanor that he passes for vital, he wears his clothes like an older man. We notice, too, his ID badge. For all his blustering authority, he’s just a cog. So here’s the cog, old before his time, vain, wanting something—more meaningless arrests, more stats, more quotas--seeing a shortcut on the desk before him--and then he shouts "Jay," ordering his underling to make it happen.

But why this scene here, several minutes removed from the result of Rawls’ decision? It’s framed by two longer, more traditional scenes. Preceding it, we see Carve and Herc, the two greenest and most brutal detectives, grab a young punk named Bodie who’s been giving them trouble. They think he’s skipped out on juvie, again, and begin to beat him for it. But he shows them a piece of paper that reveals he's been given a pass by the court. They’re incredulous. The thing is, so is Bodie. The juvenile system, he says, is a joke. Then he asks them for a ride to his grandmother’s. “Get in the back, fucknuts,” says Detective Carve.

That’s before the jacket. The scene following Rawls’ jacket features D, a mid-level man in the drug operation--something like Major Rawls--waiting for a girl who’s one of his runners to come out of a grocery. He takes her bag, looks in, pulls out some eggs, and begins dropping the eggs one by one on the sidewalk. He thinks she’s been stealing from the drug operation. But D isn’t a monster. In fact, he’s too soft for the drug trade. He has killed one, maybe two people, then almost cracked himself when presented with a (fake) picture of the kids of one his victims. The trauma of the pain he inflicts is building up. Earlier in the episode, he’s distressed by news that drug ring’s enemies has been killed—that’s the business—by torture. That, too, he’s coming to understand, is “the business.” “Let it go,” he advises a younger flunky, who can’t; and D can’t, either, so he passes “it”—the pain he feels because of the pain he’s caused—on to the girl.

Back to Rawls. Taken as a series, the three scenes are a study in authority. Nothing profound, just the observation that we pass suffering along. Not out of sadism but because the way you “let it go” is by getting it out of your system. Detectives Carve and Herc, constantly frustrated by the higher ups and by their own inability to either understand or really do anything about the crime they see, pass it on in beatings that make a mockery of the justice they say they’re not really permitted to serve. D needs to purge himself of the poison of the murder to which he’s been party. So far so simple, “down in the hole,” as the the series theme song goes, deep in the dirt of crime, that of the dealers and that of the street cops.

And Rawls, in his high office? That 25-second scene is the radicalism of The Wire. His poison is the system he’s a part of. Not its corruption; the system itself. Rawls understands that his job is not to solve crimes, it’s to “clear” them. Clear them off his desk, that is. Not justice; cleansing. Lazy, vain, amoral Rawls, high above the street, is the only one who gets what’s going on, above as below.

Jeff Sharlet is a professor of creative nonfiction at Dartmouth College and the bestselling author and editor of eight books including The Undertow, The Family, and This Brilliant Darkness, which begins in the clock tower of the Hotel Coolidge in White River Junction and ends in Norwich, where he lives with his family and creatures.